And I catch myself.

There. Barely finishing my sentence without feeling the tightness stinging in my throat. I think no one notices. I’m practiced in catching and staving it away.

There. Barely finishing my sentence without feeling the tightness stinging in my throat. I think no one notices. I’m practiced in catching and staving it away. So I shift my eyes to the next person, willing the attention and the question to rotate onward.

And the conversation continues.

There have since been two moments where I spoke this same intention aloud, and the same occurrence swept through my body — suddenly and unexpectedly and immodestly. My tears will rush out for three catches — just enough to let me know they’re there, and that I need to follow them.

Dolphins wayfind for humans adrift — maybe my tears are the same.

a zuihitsu to

I am searching for a form to carry me — not quite commonplace book, not quite morning pages, though perhaps somewhere in-between. Through hopscotch, I’ve come across zuihitsu: what is fragmented and interconnected, descriptive and evasive, understood and unknown, all at once.

a zuihitsu to zuihitsu

one

I am searching for a form to carry me — not quite commonplace book, not quite morning pages, though perhaps somewhere in-between. Through hopscotch, I’ve come across zuihitsu: what is fragmented and interconnected, descriptive and evasive, understood and unknown, all at once.

two

Is there a word in Korean for the untold?

three

There have been three occasions when I’ve looked into a stranger’s eyes, for unbroken minutes. As we shared reflections into a circle, my partner offered an observation of me — “I noticed one eye was happy. And one eye was sad.”

How strangers know our truths, before we know them ourselves.

four

I am comforted by Audre Lorde’s explanatory notes to Adrienne Rich, on the progression behind “Poetry is Not a Luxury” and “Uses of the Erotic” — “They’re part of something that’s not finished yet. I don’t know what the rest of it is, but they’re clear progressions in feeling out something connected with the first piece of prose I ever wrote. One thread in my life is the battle to preserve my perceptions — pleasant or unpleasant, painful or whatever …”

five

The personal is political.

six

The whistle and the steam transport him back to his childhood, growing up in Ulsan. He has told me before that a station and a river connected through the town; and this is the route he took at age 12, returning home on boats and trains and cash borrowed from a friend, as the war closed and bombs dropped on Tokyo.

He loses himself in fragments of vision and time and space — shakes his head.

“So — my memories are still there.”

I hold my stillness, and see where his mind connects next.

seven

“To love without knowing how to love wounds the person we love. To know how to love someone, we have to understand them. To understand, we need to listen.” -Thich Nhat Hanh

eight

Starting in the mid-1990’s, psychologists Marshall Duke and Robyn Fivush researched myth, ritual, and emotional resilience in American families. They developed a 20-question measure, called the “Do You Know?” scale.

Do you know where your grandparents grew up? Do you know where your parents met? Do you know if illness or something really terrible has ever happened in your family?

Over dozens of conversations with families and kids, they found relationships between knowledge of family history and emotional health, happiness, and self-esteem.

To know where you’ve come from — is to belong to something bigger. They call it the strength of an intergenerational self.

nine

For days after the Atlanta shootings, my body is silt and water in a storm.

And I know, without evidence, that this history is my own.

ten

I learn that Martin Luther King Jr. and Anne Frank share the same birth year. If they were alive today, they would be 92. This is the same age as Haba, though by the Korean calendar, he says he is 93.

eleven

I tear off the bottom square of a receipt, and shape it into an offering. I tuck its wing beside an amber stone, under strings of prayers dancing in the wind.

I still think of Sadako, each time I fold a paper crane.

twelve

We pause on the path, between red rocks and cacti — blowing wishes on my white hairs, in a tradition we made up, today.

thirteen

Zuihitsu is Japanese, but Sino-Japanese — put together in elements borrowed from Chinese. 随筆. In its oldest essence, it means to “follow the brush,” wherever it may lead.

a zuihitsu to zuihitsu follow the brush

Day 1

He woke on the day he died. It was a Thursday.

He woke on the day he died. It was a Thursday. For weeks, he had shimmered in the space between. Here, memory mixed with magic, brushes and breaths from a world past and beyond. He needed to call Chuck. But his broken phone could not speed dial the dead. It was time to take yobo out for dinner. They would dress well and order sandwiches for the grandkids, with good prime rib. It was almost time. He was not ready – caught in a failing submarine – sinking, down, sinking.

For moments, there was reprieve. Booky’s silly face. His mother and a warm breeze. Too swiftly the landscape would change. Pain was the length of ligaments, those final fastenings to a mortal skin. But he had lived through it all once. And now, he was free.

He drifted up to the ceiling while his caretaker was out of the room. From the farmost corner, he surveyed his resting place. The fake purple flowers were a cheap imitation of home, piled alongside doctor’s orders on the oversized vanity. The room was still hung with gold paper spirals, strung up from his 93rd birthday. He looked back at his departed form, a first glance in the mirror in the past four months. His beard was terrible, whiskers only permissible by circumstance. Bruises meant your time was coming, he remembered this from the elders of his hometown; and light patches marbled his forearms and hands. And he was thin. It accented his face – etched with a lifetime, momentarily softened in relief. He was satisfied to see that he looked peaceful. Let them find him asleep.

Shirley would be there soon, expecting to deliver his prescriptions and some soft tofu, not a last goodbye. But he would be back. This evening, he had somewhere to be.

He decided to sweep through the hallway and make a proper exit through the front door. His comrades were seated for dinner, vestiges of jello on their plates. They had been amusing company these past two months. He even had a girlfriend Kate, her hair wisped into a tight silver knot, who gifted him a card and a kiss on the head on his birthday. He wished them a grateful good riddance and swept outside.

He had never felt this light, thrummed with a beatitude like never before. Surrounded by lavender mountains and the receding hour, he drifted over the rooftops, and moved up toward the sky.

A note

My grandfather recently passed away. I’ve learned that in a Korean Buddhist tradition, the 49th day is significant – the last of the window before a soul passes from this life into the beyond. It gave me comfort to find some way of remembering – a stake in absence of knowing tradition and ritual, an anchor on the calendar as the following days began to accelerate and bleed. Yet on the 49th day, this would give way to a feeling of catastrophe, of absolute loss – cosmic and complete.

My imagining is that throughout the 49 days before moving onward, my grandfather found his way back to places and memories perhaps long buried, turning sites of provenance into sites of healing. I am in the process of re-fashioning some of the events in the essay included below, into the form above. My hope is that through writing the 49 days, we may trace the events and currents of my grandfather’s (inner and outer) life. Most days since his passing, I still feel like I don’t have the words. To honor a tremendous life – a person who is of you and part of you – feels imperfect, and impossible. Yet I’ve realized it’s these chances of remembering that are ungiven – a mark that we were loved, that we were here.

One of seven brothers and the son of the mayor: he is born in Ulsan, South Korea into Japanese colonial occupation. At age twelve, they celebrate him for admission to a prestigious high school in Tokyo. He arrives as one of two foreign students; the other is the son of a Thai king. A Korean, accepted by Shinjokoko High School. It’s unprecedented; for Koreans are despised by the Japanese. Perhaps it is to be expected then: he is demeaned. As WWII closes and bombs drop on Tokyo, the eldest of the Park brothers sounds the alarm. He returns to spend his teenage years back in Korea, fistfighting Japanese soldiers in the streets. It’s a small pride if you can steal their weapon, a victory of defiance in the bid for this country. This is the first moment he pinpoints, when articulating han as a feeling – of resentment and anger and regret, calcified into one.

Picked up off the street while selling odeng, he is enlisted in the Korean War. As families come to bribe war officers on behalf of their sons, he pushes down early bitterness as no one comes in his name. Having picked up a bit of English, he navigates the ranks to become the commander of KATUSA, the Korean Army branch augmenting the United States. Age 21, not knowing how to use a gun, he’s sent up to battle pushing the North Korean Army back. It is a future source of guilt: he survives, one of few. As the war closes, with his university burned to the ground, he turns to the US for the next chapter. He procures sponsorship and a visa through a US army major friend. He bums a box of Johnny Walker off a tall, nice Ethiopian officer gentleman, flip it on the black markets for a break. After a year of train rides and persistence for a passport, the issuing department gives in, and he proceeds to pack a trunk with books and his favorite violin. He finds passage on the President Wilson, bottom level of the ship. From Korea to Tokyo to Honolulu to SF: he stays below the water for two full weeks. But he bunks with lots of Filipinos, and the food is full and tasty.

Landing in San Francisco, he begins working the fields alongside fellow laborers from Mexico, picking peaches and grapes at 105 degrees. 4:30 AM wakeup, get breakfast and a lunch bag and load up on the truck. You’re lucky to pick peaches, for a bit of shadow from the heat. But pick the wrong shadow, and you’ll be in with the bees. Saving up at 90 cents an hour, he applies for university. Harvard responds with an acceptance letter and financial paperwork – confounded, he fills out fake information that is declined. The University of Michigan requests no financial statements, and so it is to the Midwest that he makes his way.

Journeying on the Greyhound, he chooses between white and black bathrooms in Albuquerque; and gets bounced between the front and back of the bus. After three days without stretching, he can’t walk or feel his feet. Arriving in Ann Arbor, his mind starts to take inventory: shelter. Food. Clothing. He starts to solve for a plan, need by need. He takes lodging on Oswego Street, bartering with two old ladies to live in and shovel snow. His room is the patio with plastic vinyl stapled up for walls – cold like hell. He finds a job dishwashing in exchange for three square meals. He takes the graveyard shift at the hospital, cranking the service elevator to descend into the basement morgue. At night he studies, alongside the patients that he labeled and brought down during the day. These are the stories that surface, when asked a decade ago, and now. When asked why these are the stories that he remembers, he answers with a word: “pain.”

Yet it is in the Midwest where he meets my grandmother, and where they welcome their first son. It is in Chicago where he gets his first job after graduation. It is in New York where he becomes temporarily stateless, trading his Korean passport for US citizenship and a job sponsored overseas. This opens over a decade of good life, some of their fondest years, working as an expatriate manager in Yokohama, Japan. Yet today, he wishes to die in Ulsan, in the place where he was born. Like animals returning, he says, it’s a natural thing. It’s a foregone yearning; there is no way he can.

Moving back to the State in the 70’s, he navigates work with Boeing and Hughes Aircraft, the CIA, and an opened-and-closed gyro restaurant on the side. In aerospace, as one of few Asian employees, a department manager finally informs him that he is severely underpaid. These years form the bulk of his Social Security check today. As he moves into his winter and begin painstakingly paying for care, he grips harder at his pride. No help. No charity. He insists on reimbursing us for groceries. Yet finance remains one of his demons. An insecurity, a regret. In a capitalist country, he says, there is a beautiful retirement and a terrible retirement. It is his SSI payment that is not enough to live beautifully, as the only Asian couple in this senior living building. It is his SSI payment that disqualifies him from the government-subsidized community centers in Chinatown, some of the sole places with an Asian American elder community. There is a gap between the line and the ceiling.

Having raised their children, celebrated graduations and marriages and grandchildren on the way: to Korea, they decide to retire, in a house out in the country. It is a season of Buddhism and temple visits for my grandmother; and of matching vests with the Contax camera club for my grandfather. But one day, they both return from Korea. When I ask my mother, she says she doesn’t know why. But wherever they are, she says, they’re never happy.

And so the moves grow shorter, slower, less willful. Between our house and their own apartment nearby, my sister and I are the beneficiaries of homecooked meals and rides after school. Until the day comes that they can’t make it up the stairs anymore, and move into a spot on the ground floor. Until the day comes that my mother finalizes her divorce and moves to Nevada, and moves my grandparents in with her. Until the day comes that no one can stand each other, and they move to a subsidized apartment on their own. Until the day comes when they can no longer get up when they fall, and my mother convinces them to pay the $3000 a month to move into assisted living. It’s a narrow one bedroom, with a looming price tag for the day we need to pay for more care. Some days, my grandfather says he ought to jump out the window rather than pay this much money for a submarine.

The days move slowly. There are hours spent sitting by the window in his chair. “Music,” he tells me, “the only thing that calms my emotions.” He alternates his favorites on repeat. One day, it is Jang Sa-ik’s latest hit: a song of yearning for home, a place where the wild rose only grows. The Tennessee Waltz surfaces – a big hit in his college town in Korea, an ode to Patti Page before the war. Recurringly, it is Andrea Bocelli and Helene Fischer: “Time to Say Goodbye.”

He tells me the prominent song each time I come to visit, but begin to falter with the names. Patti Pat. Something Fischer. “I’m on the last page, of my life,” he says. “I just want to know what I’m writing in this chapter.” He returns to this refrain, but the words similarly begin to morph and slip away.

How do you live a story as it’s still being written? 67 years after leaving Korea: what do we leave behind? As I capture as best I can, woven into these words is my hope for uncovering a reply.

excerpts of the 100th day

One day, Halmuni walked into a temple. She chose Buddhism from that day on. The people at church say they’re good Christians, but not really. Their actions said otherwise. This is a running streak in our family, a bristle at inauthenticity.

One day, Halmuni walked into a temple. She chose Buddhism from that day on. The people at church say they’re good Christians, but not really. Their actions said otherwise. This is a running streak in our family, a bristle at inauthenticity.

As we move my grandparents into their penultimate apartment, we unpack ornaments that might make it feel closer to home. We place a glazen Buddha on the shelf, its palm up in the mudra of teaching. Halmuni gifts me another Buddha head dusted lavender grey, saying she doesn’t need so many things. The order of their belongings shrank with each move, and those were many.

She was not so sentimental, sometimes tossing the tchotchkes we brought her on our travels. Mom rescued them if she arrived in time to detect the discarded act. One day last summer, she found the rest of Haba’s clothes in the kitchen trash bin, overflowing. For my grandmother, it was a gesture of mourning and practicality. Seeing his belongings on the other side of the room continued to sadden her – a reminder that he was gone, that she was lonely.

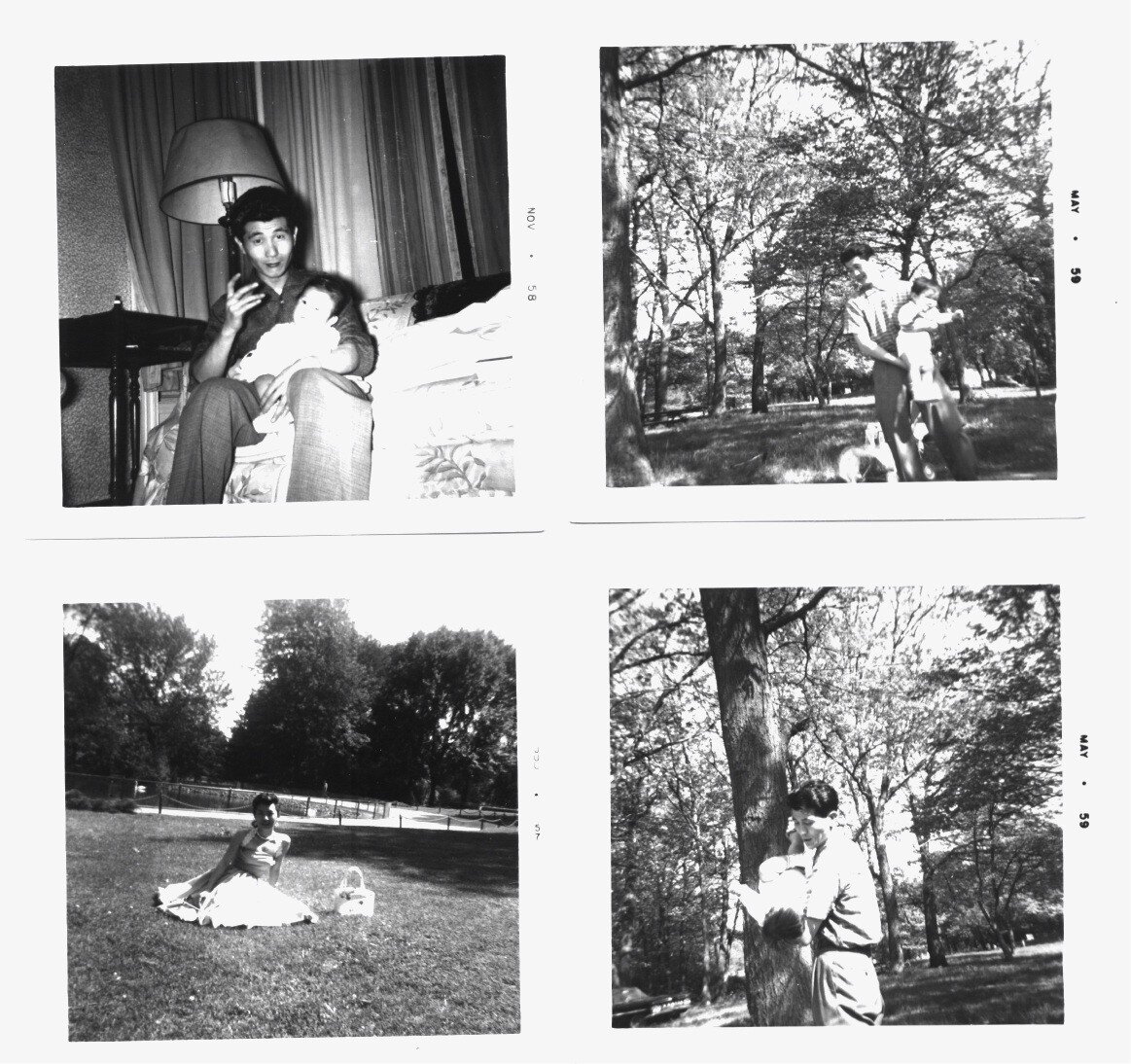

13 months later, we begin to pack again for Halmuni’s final move. She dismisses most momentos one by one, until I bring her a final frame. It is a small black and white photo of her and a friend, smiling in the youth of their early 20’s. It sat on the entryway table as aides passed through each day. They often asked us if it was her. She was beautiful. She still is.

We knew little about the photo, only that it contained a friend and a past not spoken to. To my surprise, it meets her cutoff. This is the only photo she keeps.

The friend in the photo was Anna, we learn when Aunt Robin comes to visit. Anna Shin, the one who charted the plan: they would marry American G.I.’s and move to the United States. Beauty was survival, a ticket out of a post-war country. They left Seoul in 1953 and arrived in the Midwest.

Halmuni traveled to the U.S. alone, stepping out at the bus station to meet her new in-laws in a smart suit, heels, and hat with handbag to match. She and Anna would visit each other the distance across Michigan and Missouri. She took a greyhound one day, stepped up to a bus segregated by color and asked the conductor where she should sit. I can only imagine he was stumped by this young Korean woman standing five feet tall. He pulled down the jumpseat to his right. You can sit right here.

We find her and Anna’s photo again in the box, three months unopened, as Mom gathers Halmuni’s belongings from the group home. The funeral home director has given us instructions that we can send special objects with her in the cremation, provided they are not fireworks, gas canisters, or other hazards prone to explosion.

What do you think of this photo? She seemed to like this one. Its history gives us pause. I wonder aloud what is best to carry into the afterlife, or to set away for a new beginning.

We keep the photo aside. Instead, we find a circle of prayer beads tucked away in her purse beside her wallet and a tiny bamboo mimikaki. Mom brings it to the crematory alongside sunflowers, our letters, and a wish folded into a paper crane. She slips the beads onto Halmuni’s wrist and sends it up with her, into the smoke and the air.

Sunday is the third day since Halmuni has begun to wean off food and onto morphine. Uncle John comes to pay his respects in the morning. He has always had a striking resemblance with Haba, just 11 years younger but with an alternating buzzcut or ponytail.

He had been excommunicated from the Park brothers long ago, had not seen my grandparents in years. He did not visit in Haba’s final days, nor on the 49th day after. Perhaps he thought it would be unwanted, a final affront to his brother’s sanctity. Instead he texted three words to us, our first teaching: Namu Amita Bul.

He arrives on Sunday promptly on time, just as Haba would have, and greets Halmuni softly in Korean. She does not respond outwardly. It is the third day since she has settled into a relative silence. But they say she can hear us – our hearing is one of the last senses to leave.

I was happy that he could offer a message in her first language. Over the recent years, she would occasionally lapse back into Korean, sometimes with no distinguishment between English, Korean, and Japanese. We had always spoken with her in English, and this served a mild slap to reality. I now wonder what she simply did not express to us, because of what the language could not hold.

Perhaps this has been part of the devastation – a fear that in this last and crucial window, we could not meet her in her chosen tradition. A final blow to all that we could not ask, could not understand, would never know.

We sit a while longer around her bed, Uncle John perched in a foldout walker next to the pulsing oxygen machine. Like Halmuni, he has alternated between religions – originally Buddhist, baptised Catholic, and now somewhere in between. But he shrugs. Don’t I look more like a Buddhist? On his left forearm, he shows me the tattoos of his Dharma name and Korean name, inked beside the visage of a woman he had loved, her hair flowing and breasts bare.

He tells us that at the tail of Mu Ryang San, Dancing Dragon Mountain, there is a temple there. In these mountains of Ulsan, generations of the Park family lay to rest. I realize it is his and Haba’s generation where the pattern breaks – just like an X drawn through their birth papers in the Korean government’s records of our family tree.

Originally, our family is Buddhist, he tells us. We are Buddhist.

It rings like a remembering.

On the 8th day after her passing, I wake in the early morning and cannot go back to sleep. It was not very explainable — I had gotten the least rest the night prior, as we woke early for the temple and Halmuni’s 7th day ceremony. Only with a bit of lucidity do I realize that these hours marked a full week since her last night on this earth — the hours of awakeness I had wished for, only 7 days too late.

I spent those 7 days mostly in silence — phone off, lighting a prayer and meditating each day. The dailiness of a modern environment, its distractions and chores and the constancy of it all, felt maddening and inescapable. It made me want to wish myself to a place where it could all melt away.

In the passing of those early hours, I give myself permission to return to my ego. I had been struggling in a limbo somewhere between meditation and prayer. Acceptance and grief felt at odds with each other, and I was caught in between.

I find myself wanting to sweat, to return to the temazcal. There is a parallel tradition in the Korean hanjeungmak — saunas historically fashioned from burning pine and domes of stone, and maintained by Buddhist monks. The outpost of the tradition today has evidently been converted into the Korean spa.

We settle for the sole Korean bathhouse in the Vegas area, and drive 12 miles up to Flamingo on Friday early evening. The baths are lukewarm, and the only other visitors are tourists passing time after a hotel check-out off the Strip. But there is a room with wood benches and a small portal, puffing the room full of pine. I enter, and place myself directly in front of the steam.

My mother’s brother passed away in 2009 with lung cancer. My last memory of him is from a family reunion in Huntingdon Beach, the first and only one in my lifetime. The adults must have known this was coming, planned it so we could all be together at least once. It was a significant occasion, not least because it is the trip where an ocean wave tipped me over and dislocated my knee. My Uncle Chuck was the one to get me, running into the waves and scooping me up so we could return to shore. An ER visit later, my knee remained swollen to the size of a coconut for the rest of the day.

He passed away in Honolulu, where he and his family were living at the time. The immediate kin traveled to be there for the days leading up and following. Halmuni was in anguish. His death muted her. She emerged, never the same.

Halmuni swore to stay the 49 days following at the temple in Palolo Valley, named Mu-Ryang-Sa for its broken ridge. It was an old tradition, where one stayed and prayed for the safe passage of their loved one across the 49 day journey to the beyond.

I later learn she broke all the rules during her stay, requesting the family bring her rations of Lay’s potato chips and original Coca-Cola, full sugar. She was given a grand beautiful room for the duration of her visit, and she filled it each day with curls of cigarette smoke. When they picked her up at the close of the 49 days, her first demand was for meat. They went for hamburgers, and she complained of the trials of beansprouts and a vegetarian diet on one’s digestion.

In the days of her transitioning, it occurs to me to begin preparing as if for ceremony: no caffeine, no alcohol, no meat. I begin to wonder if I could, if I should, carry out the 49 days for her, just as she had done for Uncle Chuck. It feels both jinx to think ahead, and necessary to manifest the option. I decide to wait until I can consult with the monk. It had been over a year since we had last seen her, when she performed the 49th day ceremony for Haba last spring. I text her on a Sunday asking if she would visit Halmuni, and she agrees to come that same week.

There is a memory of me at about one year old, walking with Halmuni to a temple for the first time. We walked beneath the rooftop’s wings and stood on the temple’s stone platform. It overlooked what felt like a vast lookout at the top of the hill, sloping into winding trees.

It was in 1994 when news spread throughout the Korean temple community. A temple in the Jogye order had been erected in the mountains of Tehachapi, California, and was now open for visiting. Mom recounts waiting in the car as Haba and Halmuni offered their respects — a short while until they said, gaja. Let’s go.

I hear this word for the first in a long time at Haba’s viewing at the crematory. Halmuni shuffles to Haba, holds his hand. He’s so cold. Like ice. She pauses. The suit you picked out is very nice. Pause. When they gonna cremanate him? Mom clarifies that they are waiting for the permits, that it won’t be today. Gaja. Let’s go.

It is for Haba’s 49th day ceremony that we get in touch with the temple in Tehachapi again. With some Googling in the immediate days of his passing, searching for Korean Buddhist temple options had drawn up blanks. Mom found a Thai temple in the Vegas area willing to perform the 7 day ceremony. The monks are hospitable, they say we can come sit for prayer anytime. They guide us into a hallway connecting the main hall and backrooms, and we talk at the mouth of a kitchen. A shadow shimmers behind me.

The visit ends with me inevitably in tears, wanting Haba to have a tradition closer to his own for the 49th day. From somewhere, comes the memory of the temple in Tehachapi. I wonder if we can find it, if it’s still there. I find the website and phone number online — all in Korean, but evidently still operating. A woman picks up on the first ring.

Yesterday was the 100th day since Halmuni passed from this earth.

They say there is a window of 49 days for a soul to pass through, from this life into the beyond. Some families observe for more, and some souls move with less. I feel Halmuni may have moved on quickly. Perhaps even before the 7th day, she was gone. In her final moments, tears streamed like I’ve never seen. Those last days in limbo, caught between here and the world of spirit and memory, were maybe enough of a plunge into the past — that she had had enough, that she was ready. Gaja. Let’s go. Like a flame dissolved to smoke.

In her lifetime, she chose her country, her marriage, her faith, her name. She traveled alone the distance from Seoul to the Midwest; she left a good-for-nothing marriage behind. She crossed out the names that didn’t suit her, made a fire in the backyard and burned photos of a life that was no longer hers. One day, she walked off the streets of Los Angeles and into a temple. She chose it as her own.

Across these 49 days, I am coming to understand that what she gave us is not an inheritance of tradition, but the inheritance to choose. It is the gift that we make this life — we decide what we carry with us and what we leave behind.

I am still choosing how I remember, and in what I believe. There is so much that cannot fit in small spaces. But for these 100 days and more, I am choosing to write.

Halmuni, we love you forever. May you be safe, happy, healthy, and free.

Chung Cha Park, 1932 - 2023